Ever heard the phrase, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country”? This powerful statement is a classic example of chiasmus. It flips ideas to create emphasis and memorability. But why does this technique resonate so deeply with us?

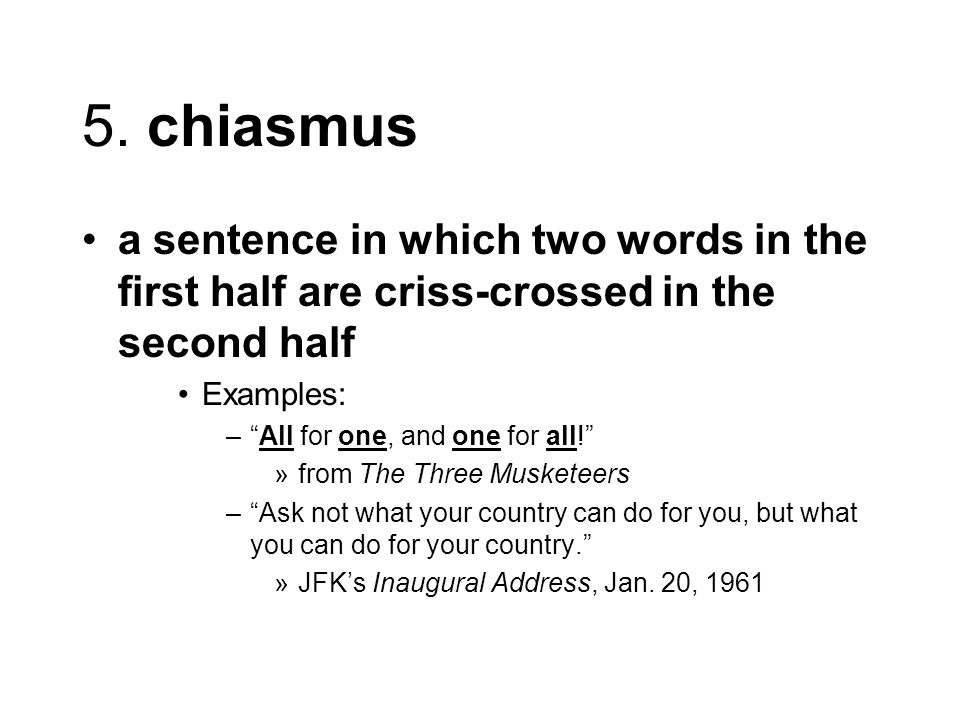

Understanding Chiasmus

Chiasmus serves as a powerful rhetorical device that focuses on the arrangement of words and phrases. It creates a mirrored structure, enhancing the impact of expressions and making them memorable.

Definition of Chiasmus

Chiasmus is a figure of speech where two or more clauses are balanced against each other by the reversal of their structures. For instance, “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” This structure emphasizes key ideas while engaging readers. It’s not just about wordplay; it’s about creating resonance within language itself.

Historical Background

The use of chiasmus dates back to ancient Greece and Rome. Think about how Aristotle employed it in rhetoric or how Cicero used it in speeches. These historical roots show its significance across time. Even famous literary works, like those from Shakespeare and John Milton, feature chiasmic structures. The enduring nature of this device highlights its effectiveness in communication throughout history.

Notable Examples of Chiasmus

Chiasmus appears in various forms across literature and speeches, enhancing the impact of ideas. Here are some notable examples that exemplify this rhetorical device.

Literary Examples

- “Never let a Fool Kiss You or a Kiss Fool You.”

This phrase highlights the reversal between “fool” and “kiss,” creating a memorable statement about relationships.

- “I meant what I said and I said what I meant.”

Dr. Seuss uses chiasmus to emphasize sincerity, reinforcing the connection between intention and communication.

- “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Martin Luther King Jr. effectively illustrates interconnectedness through this mirrored structure, stressing universal justice.

- “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

John F. Kennedy’s iconic phrase urges individual contribution by reversing the focus from self to nation.

- “We shape our buildings; thereafter, they shape us.”

Winston Churchill emphasizes reciprocal influence in society and architecture with this powerful chiasmus.

- “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

John F. Kennedy again showcases balance in negotiation dynamics, encouraging courage while maintaining perspective on power relations.

Each example serves as a testament to how chiasmus enhances meaning and memorability in both literature and public speaking, making ideas resonate more deeply with audiences.

Analyzing the Effectiveness of Chiasmus

Chiasmus serves as a powerful tool in enhancing communication. By reversing structures, it creates memorable phrases that stick with audiences.

Impact on Rhetoric

Chiasmus adds emphasis and clarity to arguments. It shapes how ideas resonate with listeners. For instance, when Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools,” he highlighted unity’s importance through its mirrored structure. This technique not only captures attention but also reinforces key messages effectively.

Memory and Persuasion

Chiasmus significantly enhances memorability. Phrases structured this way are easier to recall, which improves persuasion. Take Winston Churchill’s statement: “Never give in—never, never, never give in.” Its repetitive yet inverted format makes it unforgettable. Moreover, such patterns engage the audience intellectually and emotionally, fostering deeper connections to the message being conveyed.

Creative Uses of Chiasmus

Chiasmus appears in various forms, enriching both poetry and everyday language. Its mirrored structure captivates audiences, making messages memorable.

In Poetry

Poets frequently employ chiasmus to create rhythm and emphasize themes. For instance, “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” from Shakespeare’s Macbeth juxtaposes opposing ideas, enhancing the play’s dark atmosphere. Another example includes John Keats’ line “A thing of beauty is a joy forever; its loveliness increases; it will never pass into nothingness,” which reflects on the enduring nature of beauty through reversal. Poets use this technique to deepen emotional resonance and draw readers in.

In Everyday Language

Chiasmus often emerges in daily speech, adding flair to conversations. Consider the phrase “You can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the boy.” This familiar saying highlights how roots shape identity. Another example is “We do not remember days; we remember moments,” which encapsulates human experience effectively. You might hear politicians or speakers using chiasmus for impact—like when one says “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” This style engages listeners by emphasizing key points dynamically.